- Home

- Sarah Zettel

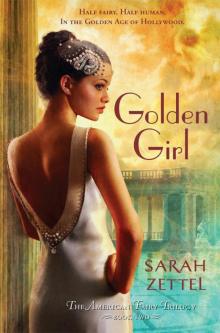

Golden Girl

Golden Girl Read online

Also by Sarah Zettel

Dust Girl

This is a work of fiction. All incidents and dialogue, and all characters with the exception of some well-known historical and public figures, are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Where real-life historical or public figures appear, the situations, incidents, and dialogues concerning those persons are fictional and are not intended to depict actual events or to change the fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2013 by Sarah Zettel

Jacket art copyright © 2013 by Juliana Kolesova

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Random House and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zettel, Sarah.

Golden girl / Sarah Zettel. — First edition.

pages cm. — (The American fairy trilogy; book 2)

Summary: As a child of prophecy and daughter of the legitimate heir to the Seelie throne, fourteen-year-old Callie poses a huge threat to the warring fae factions who have attached themselves to the most powerful people in 1930s Hollywood.

eISBN: 978-0-375-98319-1

[1. Fairies—Fiction. 2. Magic—Fiction. 3. Racially mixed people—Fiction.

4. Hollywood (Los Angeles, Calif.)—History—20th century—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.Z448Go 2013[Fic]—dc23 2013006238

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

To the Makers of Movies, the hits and the flops, the found and the lost, in Hollywood and around the world. Thank you.

Sincerely,

A Grateful Fan

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

1. Someone to Watch Over Me

2. The Show Must Go On

3. Gonna Trouble the Waters

4. Fit the Battle

5. He’s Comin’ Back to Call Me

6. Come to Keep Me Company

7. Shall We Dance?

8. Nice Work If You Can Get It

9. Just a Simple Walk

10. Then We Must Part

11. The Folks Back Home

12. Come Callin’

13. I My Loved Ones’ Watch Am Keeping

14. Gonna Steal Away

15. Comin’ for to Carry

16. Like a Motherless Child

17. That Bright World to Which I Go

18. Jacob’s Ladder

19. The Trouble I’ve Seen

20. Do You Call That a Sister?

21. Where Are You Goin’ Now?

22. Climbin’ Up the Mountain

23. Take That Away from Me

24. Your Castles Come Tumblin’ Down

Author’s Note

Playlist: The Spirituals

Playlist: The Gershwins

Watch List

About the Author

1

Someone to Watch Over Me

Los Angeles, California, May 1, 1935

Once upon a time in Kansas, there was a normal girl called Callie. I thought she was me. I’d been told all my life she was me.

Turns out, all my life I’d been lied to. Turns out, I was about as far from a normal girl as you could get. I wasn’t even human. Not all the way, anyhow. My father, Daniel LeRoux, who’d run out on my mother before I was born, wasn’t just a piano player; he was a prince of the fairies. The Unseelie court fairies, to be specific. He hadn’t run out on my mama for any of the usual reasons. He had gone to renounce the throne so they could get married.

But he never came back, and I grew up with just Mama in the Imperial Hotel in Slow Run, Kansas. Times were worse than bad because the rain had stopped and the dust had come to cover Kansas. I guess Mama decided all that truth—my being half a fairy, or having magic in my bones, or waiting on my father to get back from telling his Unseelie parents he wasn’t taking up the family business of being royalty—was kind of a lot to lay on a girl stuck out in the Dust Bowl. I didn’t know for sure why she hadn’t told me about Papa and the rest of it. By the time I found out, Mama had vanished too, in the middle of the biggest dust storm the world had ever seen. But it wasn’t the dust that got her; it was the fairies. The bright, shining ones. The Seelies.

Now I was out looking for Mama, and Papa, and the rest of the truth about myself. As you’ve probably figured, that was a tall order, and a long road. So far, it had taken me all the way to Los Angeles, California. I had no idea how far it was going to take me before I hit the end.

“Callie LeRoux, where are you going?”

I froze on the stairs and looked down at my landlady. Mrs. Constantine was big and broad, with black hair, sandy skin, a hook nose, raw hands, and the sharpest pair of ears known to man. She ran a boardinghouse for families and “respectable” single ladies, and puffed up when she got angry or proud. She was also blocking the stairway I had been trying to sneak down.

“Sorry, Mrs. Constantine,” I said, trying not to squirm. “I’ve got to get to the streetcar. I’m going to see about a job today.”

“A job?” My landlady squinted around to see if I had my suitcase with me. When she didn’t see me with anything more than a pair of high-heeled shoes from the mission store and the blue suit I’d been up all night stitching on so it mostly fit, she gave way.

“Well, you’d better get going, then, and you can drop the letters in the box on your way.”

“Yes, Mrs. Constantine.” I picked up the envelopes on the table in the hall and tucked them into my battered blue handbag, which almost matched the suit. The white gloves I’d bleached to within an inch of their lives stretched tight over my country-girl fingers. I’d have to remember to keep the palms turned in so nobody could see how worn out they were. I settled my blue straw hat into place over my black hair. I might know I was half fairy, but I was also the daughter of a brown-skinned man. People in Los Angeles didn’t take as much offense at that sort of thing as they did back in Kansas, but they weren’t all that keen on it either. Most days it was easier to try to pass for white. I had what mama had called “good skin,” meaning it was pale, and “good eyes,” meaning they were a kind of stormy blue-gray. It was my hair that I had to be careful with. I’d washed it the night before with lye water and lemon juice, like Mama had taught me, but that hadn’t made it any lighter or softer. So far, the French twist I’d spent half an hour before sunup wrestling into place was holding.

As I watched my reflection in the hall mirror, I tried to find a way to hold my face that didn’t show the guilt so plainly. I wasn’t going out about any job. I was going to try to sneak into the biggest movie studio in the country.

“Now, just one minute, Miss Callie.”

I spun around on my crooked heel, and had to catch myself against the wall. Mrs. Constantine frowned again. She was coming up the hall carrying a white napkin bundle.

“You can’t go for a job without something to eat.” She pushed the bundle into my hand and then straightened my jacket shoulders. We both pretended she didn’t notice I’d stuffed my brassiere with tissues to help cover up the fact I was still only fourteen. “Don’t forget to drop off those letters. You want your people to know you’re safe, don’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am. Thank you.” I scooted out t

he front door before she could say anything more about me or my family. I was glad for the hot biscuit she’d wrapped in that napkin, though, and the apricot jam.

When I stopped in front of the mailbox, I sorted through the letters and pulled out one to stuff back into my purse. I’d written that one with Mrs. Constantine standing over my shoulder. It was a happy letter, saying how I’d made it to the city just fine, and how Mama didn’t need to worry about me because I’d found a clean, respectable boardinghouse and everybody was being so nice and friendly. I’d addressed it to the Imperial Hotel in Slow Run, Kansas, and borrowed a stamp. Mrs. Constantine beamed as she handed it over, sure she was doing her job helping to look out for me.

But there was nobody back at the Imperial, and there wouldn’t be until I got my parents out of wherever the Seelie fairies had taken them. Problem was, I only had hints about where that might be. They weren’t very good hints either. One of the biggest problems with fairies and magic people is that they don’t talk in straight lines, even if they’re on your side, which, believe me, they mostly aren’t. I’d been told my folks were locked up in the golden mountains of the west, above the valley of smoke, in the house of St. Simon, where no saint has ever been.

You see what I mean? And that was from somebody who was actually trying to help.

Fortunately, there aren’t too many places you can mean when you say “the golden mountains of the west.” That’s pretty much got to be California, so that was why we’d come out here. “We” is me and Jack Holland. Jack’s my best friend. Without him I wouldn’t have made it ten feet from my own door. On the other hand, without me he’d probably be on another chain gang somewhere, so I guess it mostly evens out.

Now, California’s a big place. It’s got a lot of hills and a lot of gold, but another thing I learned about fairies is that they like music and bright lights, pretty people and dancing, and all those other things that are beautiful about human beings. And where are the brightest lights, the best music, and the prettiest people in the whole world?

Hollywood, and the movie studios. Me and Jack both figured if there were fairies hanging around anywhere in California, that’s where we’d pick up their trail. After that … well, like Jack said, we’d cross that bridge when we came to it.

See, fairies live in a world of their own. Maybe it’s a bunch of worlds; I’m not sure about that part yet. But they don’t seem to like it there much, because they want to get into our world awful badly. To do this, they need a special kind of gate between their world and the human world. If I could find one of those gates, I could open it or close it. That was the extra-special magic I’d been born holding. That magic is so special, in fact, the fairies have a prophecy about me. They say: See her now, daughter of three worlds. See her now, three roads to choose. Where she goes, where she stays, where she stands, there shall the gates be closed.

I’ve got no idea what that means. Jack says that’s normal for prophecies. He says that until they come true nobody knows what a prophecy’s actually about. If you ask me, that makes them pretty pointless. But pointless or not, this particular prophecy caused me all kinds of trouble. The fairies get all worked up into a tizzy by that “where she goes, where she stays, where she stands, there shall the gates be closed” part, and they keep trying to get me onto their side, either by threats or by tricks. Except I don’t want to side with any fairies. I just want to find my parents and get a chance to find out what being a normal person is all about.

Now, my idea for starting our search through the studios had been to join up with one of the tour groups. Jack, being Jack, had a different idea. He spent most of our last fifty cents on a clean shirt at the secondhand store and the rest on a bath at a flophouse. Then he just walked right through the front door of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which is the biggest movie studio in Hollywood, and asked for a job. You could have knocked me over with a feather when he walked out again and said he’d gotten one. It seemed that the MGM back lot was so big, they needed boys like Jack to run scripts and messages and stuff to the different offices and movie sets there. One glance at Jack’s mile-long legs had apparently sealed the deal. He was on the back lot now, and I was following after so he could sneak me in. We didn’t figure we could wander around looking like the kids we were without somebody getting suspicious, so I had to pretend to be a secretary or something like that, and that’s why I was all dressed up trying to appear older than I was, and wearing exactly one piece of clothing that had never belonged to anybody else: I had on my first and only pair of silk stockings. I wished I could stop being nervous long enough to enjoy them.

It all would’ve been lots easier if I could have just used my fairy magic. One of the things I can do with that magic is make people see exactly what they wish to see. But there’s a problem: when I use my magic, the other fairies can feel it. This was really bad, because it wasn’t just my parents those fairies were after. They wanted me too. So using magic was out. We were going to have to do this the hard way.

The sun was just starting to come up over the hills, but the trolley to Culver City was already full by the time it pulled into my stop. I had to hang on to a strap the whole way out, and I wondered if the high heels had been such a good idea. At first I stood there trying to paste a look on my face that said I did this every day. That didn’t work so well, so I just concentrated on keeping my head down. I knew nobody was looking at me. Fairies weren’t the only ones who lived in their own world. Everybody else on that rattling, squeaking trolley was reading the paper or a book, or just staring out the windows at Los Angeles rolling past. Nobody knew me from Adam’s off ox here, and they cared even less about me. But that didn’t matter. My layers of disguise from the mission store felt paper-thin over the Callie LeRoux underneath, and a whole hive’s worth of questions was buzzing around inside my head. Like, what happened to girls who were screwy enough to try to sneak into movie studios? Probably they just got thrown out, maybe with a stern warning, and the boys who helped them get in were fired. On the other hand, the studio had all kinds of walls and fences around it, plus security guards sitting in these white houses at the gates. Maybe they’d arrest me. Us. Maybe we’d end up in jail. Did they send you out on the chain gang in California?

When I get nervous, I start to lose my hold on my fairy half. See, like all fairies, Seelie or Unseelie, my inborn magic means I can grant wishes. But magic always has another side. The other side of being able to grant wishes is that if I’m not careful, I feel any wishes being made around me. And everybody on that trolley wished for something. They wished for fame, and better jobs, and love, and for that guy the next desk over to get what was coming to him, and for a better seat on the trolley home. The fairy part of me wanted to grant those wishes. It’d be fun, and the people would be happy, and I’d get to feel all that happiness, just as clear as I could feel all those hungry wishes. I could draw the feeling inside me and use it to fill up my magic with fresh power. Then I could do anything I wanted. Anything at all.

I shoved that idea back down and tried to find something else to think about while we bounced and rattled and clanged over the rail crossing. I settled on making up a second letter to my mother. Mrs. Constantine would want to see me writing another one, and I wanted to keep Mrs. Constantine happy so she wouldn’t ask any more questions than was strictly necessary.

The next letter would start like this: Dear Mama: Hope you are well. I promise I’ll be seeing you soon. And guess what? Today I got to see a real movie studio!

I’d tell her about Los Angeles too, if I actually wrote the letter. She’d want to hear about that. It was so different from Slow Run that it might as well have been on another planet. The dust storms that had wiped out Kansas and five or six other states never reached California. The hills blocking off the empty horizon were bright green. Coconut palms, live oaks, and date trees grew everywhere, and there were more kinds of flowers than anywhere else in the world. The buildings were all clean and new, and shiny cars and clanging

trolleys filled the straight, paved streets. It was big and loud, suspicious and mean, beautiful, exciting, and confusing, and despite everything and everybody after me, I was in deep danger of falling in love with it.

But it wasn’t love I was feeling by the time I climbed off the trolley at Overland Avenue. I was halfway to being sick and all the way to being exhausted from trying to keep my brain closed to all the wishing and feeling from the other trolley passengers. It only got a little better as they spread out onto the sidewalk, because they joined a whole river of other people who had their own wishes. People came from around the world to find work here, and their skin was every shade from pink to deep black and their eyes were as many shapes and colors as you could think of. They wore all kinds of clothes: suits or overalls, pretty dresses or hotel maid uniforms, long silk coats and pants on the men from China, smocks and sandals on the men from Mexico or the Philippines. The white ladies had big floppy hats on their heads to keep their skin from turning brown, the brown ladies wore big floppy hats to keep from turning black, and the black ladies wore prim hats and white gloves so nobody would think they were anything less than respectable.

The cars and trucks that rumbled down the street belched heavy smoke into the morning air, crashing their gears and blaring horns at drivers who didn’t hit the gas quick enough when the light on the corner changed. It was going on nine o’clock. I tried to hustle down the sidewalk to get past the worst of the crowds, but the heels weren’t making that real easy, especially when I had to duck around the people who stopped to grab their breakfast off the coffee cart before they filed into the office buildings.

The offices stood on the right side of Overland. On the left side, all you could see was a tall fence, its white paint peeling off in big patches. On the other side of that fence waited the studios of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Just thinking about it doubled those butterflies inside me. All the stuff they wrote about in the magazines and the gossip columns or talked about on the radio programs—stars, fame, and glamour—it waited just on the other side of this long white fence. Maybe I’d get to see them making a movie. Maybe I’d see somebody famous. Maybe Cary Grant, or Ginger Rogers, or even Ivy Bright.

Laurel

Laurel A Mother's Lie

A Mother's Lie Playing God

Playing God Dust girl

Dust girl Sword of the Deceiver

Sword of the Deceiver Let Them Eat Stake: A Vampire Chef Novel

Let Them Eat Stake: A Vampire Chef Novel Dust Girl: The American Fairy Trilogy Book 1

Dust Girl: The American Fairy Trilogy Book 1 The Usurper's Crown

The Usurper's Crown For Camelot's Honor

For Camelot's Honor Camelot's Blood

Camelot's Blood Kingdom of Cages

Kingdom of Cages Fool's War

Fool's War Golden Girl

Golden Girl A Sorcerer’s Treason

A Sorcerer’s Treason The Firebird's Vengeance

The Firebird's Vengeance A Taste of the Nightlife

A Taste of the Nightlife Assassin's Masque (Palace of Spies Book 3)

Assassin's Masque (Palace of Spies Book 3) Reclamation

Reclamation Bad Luck Girl

Bad Luck Girl Under Camelot's Banner

Under Camelot's Banner Palace of Spies

Palace of Spies Dangerous Deceptions

Dangerous Deceptions Quiet Invasion

Quiet Invasion In Camelot’s Shadow: Book One of The Paths to Camelot Series (Prologue Fantasy)

In Camelot’s Shadow: Book One of The Paths to Camelot Series (Prologue Fantasy)